For generations, lawyers have been trained to “think like a lawyer” by applying laws to facts, identifying enforceable rights, and advocating for client outcomes. This traditional model—shaped by centuries of Western jurisprudence—positions lawyers as navigators, gladiators, or even predictors of court outcomes.

But what if winning a case isn’t enough? What if the legal system alone doesn’t fully repair harm, restore dignity, or support long-term well-being?

Restorative lawyering offers a different lens. It asks lawyers to consider not only legal outcomes but also human needs, relationships, and the broader impacts of conflict.

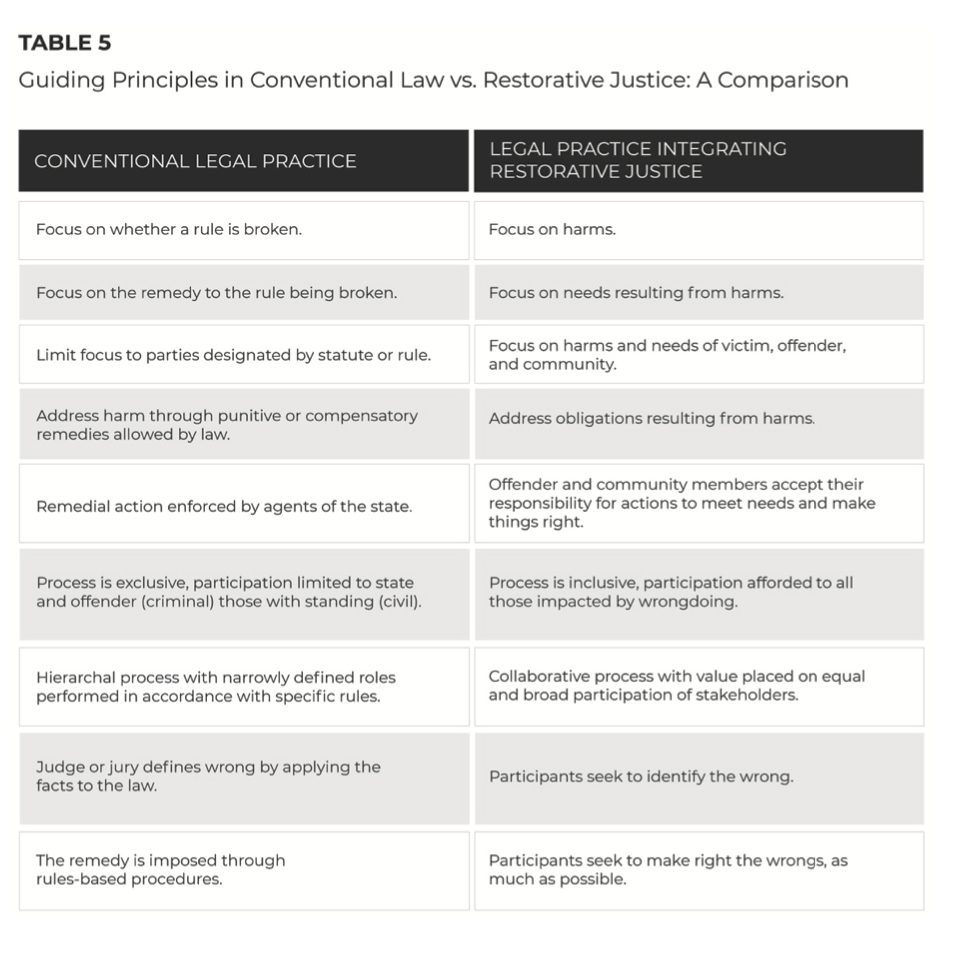

Zehr’s Principles: Framework for Restorative Lawyering

Howard Zehr, in Changing Lenses, outlines five principles that provide a framework for restorative lawyering:

Focus on harms and needs – of victims, communities, and offenders.

Address obligations resulting from those harms – not only for offenders but also for communities and society.

Use inclusive, collaborative processes – ensuring that all voices are heard.

Engage all stakeholders – victims, offenders, families, community members, and professionals.

Seek to make things as right as possible – moving beyond legal remedies to repair harm.

When applied to legal practice, these principles shift the lawyer’s role. Lawyers move from a narrow focus on rules and rights to understanding the purpose behind the law: supporting a peaceful, healthy, and prosperous community.

Collaboration and Inclusivity

Restorative lawyering emphasizes collaboration over competition. Traditional law often limits participation to those with formal legal standing. In contrast, restorative practice encourages including families, community members, and professionals who can contribute to meaningful solutions.

This approach:

Broadens perspectives and strengthens outcomes.

Encourages creativity, transparency, and accountability.

Increases the likelihood that resolutions will be sustainable.

Collaboration requires vulnerability and a willingness to step back from adversarial instincts, but it enables solutions that truly address the underlying harm.

A Broader Vision for Legal Practice

Restorative lawyering does not replace conventional law—it enhances it. It asks lawyers to:

Examine the purpose behind legal rules and regulations.

Understand the human impact of conflict.

Identify unmet needs and resulting obligations.

Engage all impacted parties in meaningful dialogue.

Support accountability, repair, and healing.

By integrating restorative principles, legal practice becomes not just transactional, but transformative. Lawyers can create outcomes that repair relationships, meet needs, and promote long-term well-being for all parties involved.

Restorative lawyering is a mindset and a practice. It challenges traditional assumptions, expands the circle of participation, and encourages lawyers to think beyond rights and duties to real-world impacts.

For a deeper exploration of restorative lawyering, my book, Becoming a Restorative Lawyer, is available through Good Media Press:

👉 https://www.goodmediapress.com/product-page/becoming-a-restorative-lawyer